|

|

THE MANUFACTURING OF ANCIENT STONE BEADS

In the

subsequent chapters, I will delve into the marvels of

ancient bead production. While this is not intended to

be a scholarly treatise, it does invite you to be

intrigued and inspired.

The intricate process of bead making, dating back to the

enigmatic Indus Valley civilization, necessitated a

division of labor, with craftsmen specializing in

different stages of manufacture. A single artisan was

unlikely to execute all the steps involved in the

creation of a bead, these being:

Sourcing

the material

Shaping

Cutting

Polishing

Drilling

In some instances, each of these steps would be

performed by a different individual. However, in other

cases - varying by location and era - an artisan might

possess expertise in several of these areas. This

compartmentalization of bead-making labor can be traced

back to the ancient

Harappan culture 2500

BC.

It underscores the earliest signs of urbanism, given

that civilization inherently requires a division of

labor.

THE SURFACE

We'll commence our exploration by studying the surface

of the bead and conclude at the bead hole. Over time,

ancient beads acquire a sort of tarnish known as patina.

Primarily, there are two types of patina: one created by

time and earth, and the other by

time and human skin.

Firstly, we'll examine what I've termed as the 'sweat of

the earth'. This patina takes shape over decades due to

the combined effects of soil, dirt, and temperature

fluctuations, triggering a chemical reaction on the

surface of the stone bead.

Excavation Patina on Ancient Beads

The term 'excavation patina' refers to the kind of

patina a bead acquires, not from wear and tear, but from

being buried underground for centuries. This patina can

be classified into two categories: one that arises from

the bead's interaction with the earth, and a more subtle

sheen formed through the bead's exposure to air over

thousands of years! This latter form can be observed in

beads found in burial caskets. The first kind of patina

I've opted to term as the 'sweat of the Earth'.

Three Kinds of Earth - Acidic, Alkaline, or Neutral

PH-Value

Primarily, there are three types of soil in which beads

can undergo their often millennia-long slumber:

Alkaline, Acidic, or PH-neutral soil.

Three Distinct Types of 'Sweat'

The ultimate appearance of an ancient stone bead is a

consequence of three types of sweat:

The sweat of human endeavor

The sweat from generations of human skin

The sweat of the Earth

CALCIFICATION - THE SWEAT OF EARTH

& BODY

Calcification

is a process that involves the depositing of calcium

salts. The calcification not only creates a unique

patina on the bead but also serves as a testament to its

age and history. The extent of calcification can provide

clues about the bead's burial conditions, including the

composition of the soil and the presence of organic

matter.

This calcification can manifest as a crust or a layer of

white or yellow coloration, depending on the other

minerals present in the soil. The texture of this

calcified layer can vary, ranging from a smooth coating

to a rough, chalky crust. The process takes place in a fascinating intersection of

natural chemistry, human history, and artistic beauty

Calcification takes Centuries

The calcification process on the surface of the beads is

slow and gradual. Over centuries, the calcium ions in

the soil solution can adhere to the surface of the bead.

Initially, this might just alter the coloration of the

bead, creating a subtle patina. However, over time, as

more and more calcium ions attach to the bead's surface,

a thicker layer of calcification can form.

This often occurs in damp

soil abundant in calcium, featuring a pH value either

below or above 7.

The Mineral Body-Shadow

In the case of ancient beads, this process can

occur when they are buried in calcium-rich environments

over long periods of time, particularly in soils rich

with decomposing organic matter like human remains.

Human bodies, along with many other organisms, have a

significant concentration of calcium, predominantly

housed in the bones and teeth. Over the course of time,

as a body naturally decomposes, the calcium along with a

variety of other minerals contained within the skeletal

structure, are gradually released and infiltrate the

surrounding soil. This particular phenomenon is commonly

described as the body's "mineral shadow", a signature

imprint left behind.

In circumstances where beads or other types of artifacts

are interred in conjunction with the body, they can

potentially come into contact with and absorb these

released calcium salts and other minerals. This exposure

often triggers a unique calcification process, distinct

from other natural or environmental calcification

processes.

|

|

|

|

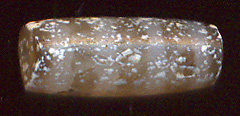

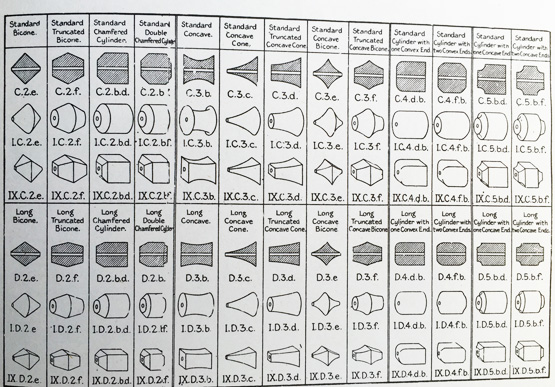

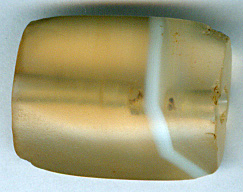

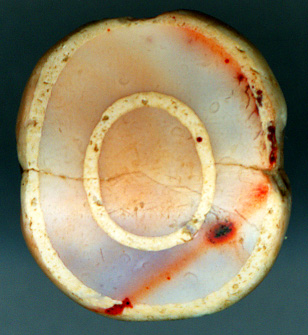

A Burial calcificated

Bead from the Indus Period. Note the thickness

of the calcified layer in the left cut side of the bead.

|

This suggests that beads

which have been ritually interred along with their

possessors, often termed "burial beads," generally

exhibit a higher degree of calcification. This type of

calcification, induced by proximity to decomposing

remains, generally results in a far more pronounced and

accelerated mineral encrustation on the surface of the

beads or artifacts, provided they are composed of a

material susceptible to such absorption. The resulting

patina not only serves as a testament to the artifact's

history but also as a tangible link to its interment

alongside human remains.

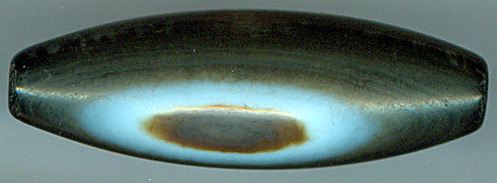

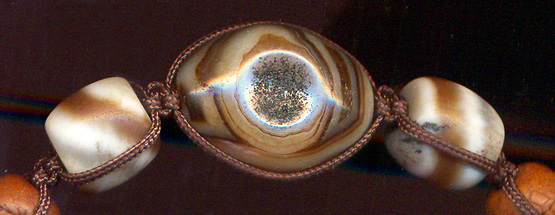

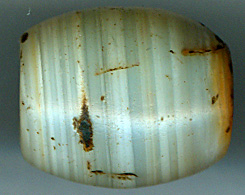

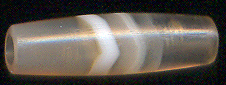

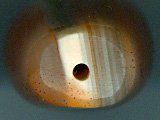

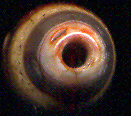

Pictured below displays an

arresting ancient agate burial eye bead. The white and yellow

tints are confined only to its surface. I'm sure you

would agree, the outcome is truly awe-inspiring! The

distinctive clouding is likely the result of minerals,

particularly calcium, permeating into the bead's surface

over an extensive period.

|

|

|

|

25 * 10 mm

A mysterious colored agate Eye Bead.

|

It is a rare occurrence for a bead to gain additional

aesthetic appeal through its interaction with the sweat

of the earth, yet a fair number of Indus beads have

derived their charm from the calcification process. This

might be attributed to the fact that calcification is a

slow and meticulous process. Over centuries, the

accumulating calcification not only transforms the

beads coloration, but also bestows it with a testament

of time, embedding in it a story of the ages it has

silently witnessed.

|

|

|

|

|

Below can observe some more ancient beads that have been colored by the soil. Note the whitish dots on the

surface of the bead. They have not contributed to the

beauty of the beads.

|

|

|

|

|

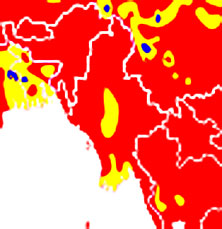

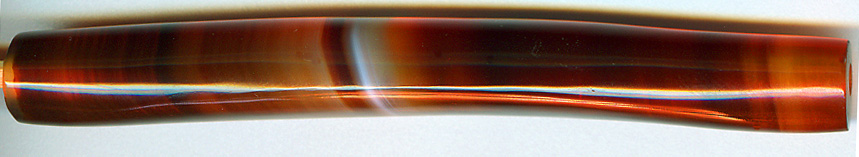

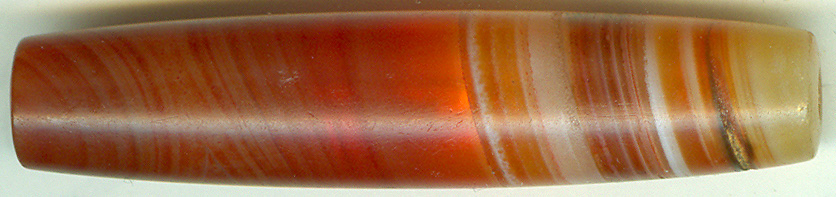

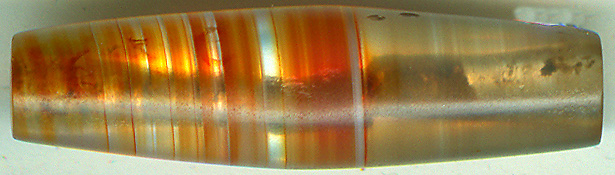

Below is an image of an expansive carnelian bead. At first

glance, this bead could easily be mistaken for a recently

crafted piece, were it not for the subtle signature

discoloration - a telltale testament to its centuries-long

slumber in the caustic embrace of acidic soil.

|

|

|

|

|

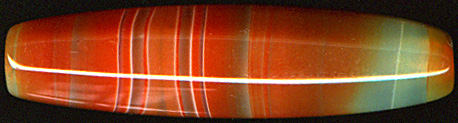

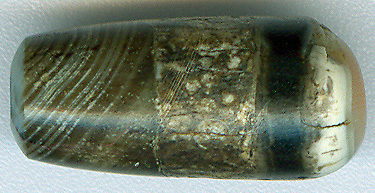

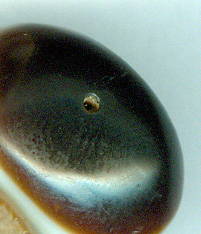

Etched Burmese carnelian bead with oil & gas patina

Featured below is

an etched, elongated carnelian bead hailing from the

lower region of the Kachin state in Burma. Here, the

intense white hue gracing the bead's surface is not a

product of the calcification processes we've previously

discussed. Instead, this bead's unique patina is a

result of a rare combination of oil, gas, and pressure

over time, leading to a distinctive and stunning

transformation of the original carnelian surface.

|

|

|

|

63 * 10,5 mm

|

|

Burma, being a land

abundant in natural resources such as oil and gas, hosts a unique array

of ancient beads exhibiting the discoloration illustrated above.

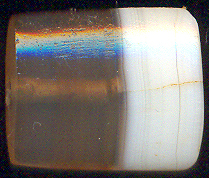

Excavation beads found in PH-neutral surroundings

In circumstances where a bead has been nestled in soil with a pH value

below or above 7, there will invariably be noticeable chemical evidence

of the bead's interaction with the earth on its surface. This would be

the case even without the chemical interaction with the

"mineral shadow". of a

corpse. Even when not overtly colored, as showcased by the beads above,

the intricate and subtle ridges crafted during the polishing process

gradually fade as the years pass.

However, in instances where beads have been slumbering in pH-neutral

soil or, more significantly, in sand, the bead's surface can appear as

if it were crafted only yesterday! The same is the case for beads found

in pots or burial caskets. In such instances, the only factors capable

of confirming whether the bead was created a millennium ago or more

recently are the sheen of the bead and the nature and quality of its

craftsmanship. Even beads that have rested in pH-neutral sand

distinguish themselves from recently crafted counterparts. They possess

a gentler shine and a more subdued reflection when subjected to an

intense light source, particularly sunlight.

|

|

|

|

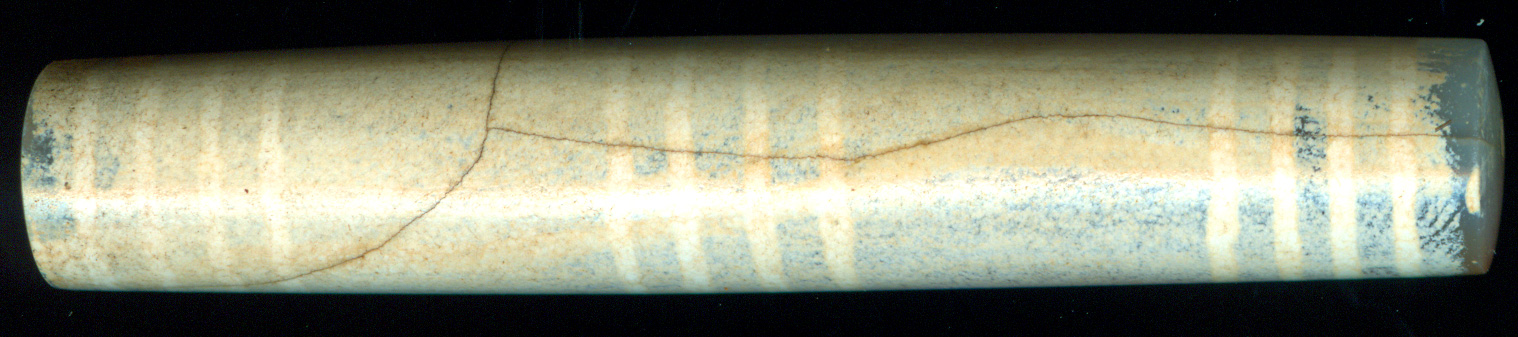

Burmese Sulemani agate bead

|

|

Displayed above is an exquisite ancient Burmese bead

unearthed from the sandy soil of Matehtilay, Maline in Burma.

Interestingly, the majority of Burma has acidic soil. Lower Burma hosts

small pockets of alkaline soil. However, the central part of Burma,

including regions like Matehtilay, encompasses extensive areas where the

sandy soil maintains a neutral pH value. In such instances, the true age

of the bead betrays itself only through its gentle sheen, referred to as

patina, and the distinct intricacies of its craftsmanship.

PH- map of Myanmar

|

|

|

|

Red = acid, blue = alkaline, yellow = neutral

|

The beads

showcased above, alongside those displayed below, have been discovered

in the indicated yellow region. In such an environment, the only

influencing factor upon the beads is the air surrounding them.

|

|

|

|

Click on picture for larger image

|

Excavation

patina

Excavation patina is a unique feature that emerges over

time, particularly in circumstances where a bead has

been buried in pH-neutral soil or safely stored in a

non-reactive container, such as a clay pot, in a place

free from sub-zero temperatures. Determining the age of

these beads can be challenging, as there may be fewer

obvious signs of age. Yet, the ceaseless interaction

with time, fluctuating humidity levels, and changing

temperatures results in the formation of a subtle and

gentle sheen or patina on the stone bead. This

understated patina softens the bead's overall

appearance, bestowing an elusive but distinct indication

of antiquity.

|

|

|

|

|

|

The image above

showcases an excavated casket of beads from the

Harappan culture. Take a moment to observe the

luster of the white and brown beads. They appear as

though they were freshly crafted. However, don't be

fooled! These are indeed ancient artifacts. It often

requires an expert's discerning eye to differentiate

between the vibrant shine of a newly made bead and the

"dusty" patina that adorns an ancient excavated one.

These

excavated beads often bear no signs of extended wear. In

many cases, they were briefly used or not used at all

before they were placed in burial caskets. These beads

served not only as symbols of the deceased's social

status, but also as talismans or even as currency for

the afterlife. At times, they were strategically

positioned in the heart of Buddhist stupas, acting as

revered relics intended to sanctify and purify the

entire structure.

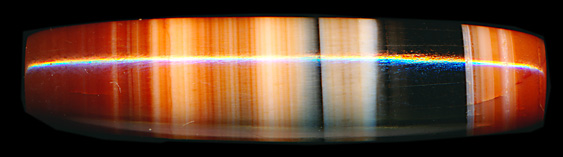

Oxidation Patina

The etched bead displayed below carries an original

oxidation patina, a quality that is difficult to

accurately represent in digital images.

Over centuries, the

interaction between the bead's surface and the

surrounding environment leads to an oxidative reaction,

which causes the formation of an oxidation patina. This

patina is essentially a thin layer that forms on the

surface of the bead due to this long-term chemical

reaction.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Oxidation patina often imparts a distinct characteristic

to the bead, lending it an air of authenticity and

historical significance. This patina is not just a

product of aging but also of the environment in which

the bead existed.

One of the

challenges in analyzing ancient beads is that it's

difficult to capture the subtle qualities of an

oxidation patina through digital images. The surface

changes are often subtle and can vary greatly in color,

texture, and depth, making it hard to convey through a

flat image. However, when observed in person, this

patina often adds an extra dimension to the bead,

serving as a testament to its journey through time.

In the case of the etched bead displayed below, the

oxidation patina tells a story of its 2,000-year-long

existence, subtly altering its surface while

highlighting its intricate etched designs.

Displayed below is

an exquisite hexagonal bead, which likely never saw any

use and is only a few centuries old. In cases like

these, determining the bead's age can pose a challenge.

We must in such cases have a deeper look at the design

of the bead.

Regardless of its exact timeline, one can't deny the

striking beauty of this bead. Its detailed craftsmanship

and unique shape offer a glimpse into the artistry and

tradition of bead making.

|

|

|

|

Antique Hexagonal carnelian bead

|

|

The

Stories in the Cracks: Age Markers of a Thousand Cold

Winters

When an agate bead has had the fortune to 'sleep'

for hundreds of years in areas where winter temperatures

dip below zero, moisture within the bead creates small,

circular cracks on its surface. This phenomenon results

from the expansion of water molecules as they transform

into ice.

Such elegant signs of age are mostly evident in beads

from the Himalayas, Afghanistan, and other regions with

frosty winters. However, beads that have been housed in

warmer climates might also occasionally showcase these

marks of age. In such situations, these cracks are most

likely produced by sudden shifts in temperature or

possibly exposure to high heat, as might be experienced

in fires from funeral pyres.

Moreover, the manifestation of these cracks also relies

on the hardness and 'porousness' of the stone. A dense

agate stone bead containing minimal water or other

chemical impurities can even endure the harsh winters of

the Himalayas without yielding to these cracks.

|

|

|

|

Bhaisayaguru beads from Afghanistan with beautiful cracks

|

In the contemporary bead market,

artificial methods are used to simulate the natural age

markings found on genuine ancient beads. One such

technique involves repeatedly transferring new beads

between a microwave oven and a freezer, inducing cracks

that superficially resemble those made naturally by cold

winters.

|

|

|

|

Fake DZI bead

|

|

Examine the Dzi bead from Taiwan in the

image above closely. You'll notice numerous small, artificially induced

indentations on the surface. These indentations aim to mimic the

appearance of ancient frost patina, but they lack the circular shape of

natural cracks. Furthermore, take note of the bead's dusty sheen,

another indication of artificial aging. Owing to their astronomical

value, Dzi beads are among the most frequently counterfeited beads in

the market. This bead, with its artificial 'cracks' and contrived sheen,

is a clear example of a counterfeit bead. As such, it is vital to be

aware of these deceptive practices when collecting or purchasing beads.

THE SWEAT

AND POLISH FROM HUMAN SKIN

Beads, particularly those of

antiquity, acquire a distinct patina over time, not solely from their

exposure to the natural elements - earth, wind, fire - but also from

consistent interaction with human skin. In essence, this is a form of

human sweat patina. This process entails the chemical reaction between

the bead's surface and the natural oils and salts found in human sweat.

The polishing of a bead doesn't end when it's removed from the tumbler

or detached from its maker's polishing stone. At that point, human skin

assumes the role of polisher. As the bead is passed down from one

generation to the next, it undergoes a slow-motion relay race,

undergoing subtle changes in texture and appearance throughout its

journey.

The human skin, in this context, acts as a soft, biological abrasive. It

gradually smoothes and polishes the bead over the years, contributing to

its final look, a look that is a constant work in progress as the bead

continues to interact with human skin.

Beads have held significant cultural and spiritual importance across

various cultures since the Neolithic era. These ancient societies often

attributed magical or mystical powers to beads. This could potentially

explain why beads were so often in contact with human skin, being worn

regularly as adornments or amulets. The human sweat patina is not just a

mark of age but a testament to the bead's intimate relationship with

human history, culture, and belief systems over centuries.

Shamanic sweat & rechargeable talismans

In ancient times, long before religion became formalized and organized,

each clan or tribe had a shaman. Serving as a conduit, the shaman

negotiated and facilitated the communication between the invisible

spirit realm and the mundane world of everyday human existence. The

wearing of beads in these societies was not a mere adornment but a

protective act - a shield against the myriad of spirits believed to

reside in caves, mountains, waterfalls, and trees in the animistic

worldview.

As time progressed, the role of the shaman evolved or was supplanted by

holy men or priests. Nevertheless, in cultures where beads were believed

to possess magical properties, it was crucial for these beads to be worn

in direct contact with the skin, preferably close to the heart.

Consequently, we see numerous ancient beads that bear the marks of

prolonged skin contact.

Holy Capital

While it wasn't only the shamans or holy men who wore beads, their

significance in religious contexts cannot be underestimated. For

instance, in India, the commonly used term for beads, "Babagoria" or

"Baba Ghori", translates to "holy man's bead", reflecting the

deep-rooted belief that these beads were primarily worn by religious

leaders. An ancient Indian scripture from the Gupta period, Vijjalagga,

even posits that a bead's value is enhanced through the act of wearing

it (Indian Beads, Shantaram B. Deo, p.15). The concept that a bead

acquires greater 'holy capital' if worn by a holy figure, be it a Sufi,

Buddhist, or Hindu saint, is prevalent even among contemporary bead

collectors.

This intricate relationship between the wearer and the bead goes beyond

mere possession. It is believed that a bead worn by a person with good

karma initiates a cyclical exchange of spiritual energy. The holy person

imbues the bead with their positive energy, which the bead then stores

and radiates back to the wearer.

It's in this context that the term

"Rechargeable Talisman" emerges - a bead isn't merely an inanimate

object, but an active participant in spiritual energy exchange, gaining,

storing, and emanating holy power.

|

|

|

|

RB 8

-

18 * 13 mm -

Hexagon

Super ancient

Proto Elamite carnelian bead -

'polished' and charged with spiritual DNA since the beginning of the bronze

age.

|

A human polishing process stretching over generations

The process of human polishing is not an

event but an epoch. One lifetime of wear isn't sufficient to imbue the

bead with the characteristic, almost skin-like shine of generations of

touch. This transformation takes several generations of contact, wear,

and polishing before a bead can fully mature in its aesthetic appeal.

Pause for a moment, and behold the bead displayed above. Its journey

across generations and lives is evident in its sheen - it is as if beads

themselves believe in the concept of reincarnation.

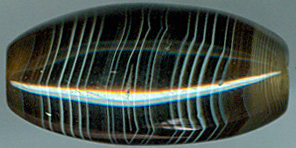

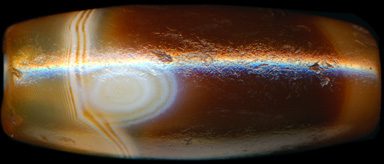

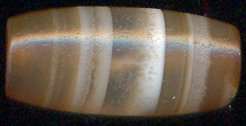

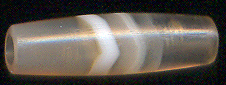

Below, you will observe a

breathtaking ancient banded agate bead. Generations of contact have

softened its surface, imparting a patina that is nothing short of a

royal seal of antiquity. This soft sheen cannot be faked, nor can it be

hastily acquired. Note also the edges of the small crack on the right

side of the bead - such signs are trustworthy indicators of authentic

age in a stone bead. Similar to how continuous waves polish stones on

the seashore, the unending encounter of human skin and bead polishes the

bead over time.

In India, there exist sacred fireplaces where the duty of keeping the

flame alive has been passed down from guru to student across countless

generations. Drawing a parallel, it is not far-fetched, especially when

considering the timeless continuity of India, to imagine that there

exist stone beads that have been in constant contact with human skin

since the dawn of civilization!

|

|

|

|

Ancient bead

worn for several generations

|

|

This revelation positions beads not merely as the oldest

form of art, but also as the most persistent and

unchanging art form in the annals of human history.

Consider this - the stone bead you see below, worn by me

in the present, could very well have adorned the neck of

a Neolithic individual some 8000 years ago. Such

continuity, such survival of beauty and significance

through thousands of years, is nothing short of

awe-inspiring. It's a testament to the enduring human

spirit and the timeless allure of personal adornment,

making beads a physical embodiment of our collective

human story. If this doesn't inspire awe, it's hard to

imagine what will.

|

|

|

|

Neolithic bead

|

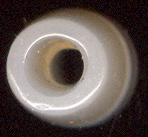

Indeed, the contrast can be stark. The Luk Mik bead

pictured below has a decidedly new sheen. While it may

be difficult to discern in a web photograph, there's a

distinct difference that becomes evident upon closer

examination. The surface of the bead gleams brightly,

untouched by the gentle abrasion of human skin and the

wear of time. It acts almost like a mirror, reflecting

light directly rather than softly diffusing it.

|

|

|

|

New

Luk Mik bead

|

|

This is a stark contrast to the other bead displayed

earlier. The older, ancient beads have a subtle, soft

reflection that comes from years of interaction with the

world and their wearers. They do not shine with the

stark, mirror-like quality of the newer beads.

This difference in shine is one of the key aspects used

to distinguish between new and ancient beads. Through

comparison, one can see how the mirror-like reflection

of the newer beads contrasts with the softer, diffused

glow of the ancient ones, a testimony to their

respective histories.

|

|

|

|

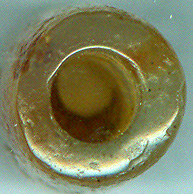

New bead

|

Indeed, the distinction

in the quality of reflection between ancient and new beads is

significant. Ancient beads have a more subdued glow; their surface,

polished by time and human touch, diffuses light rather than reflecting

it directly. This results in a gentler, warmer, and arguably more

profound sheen, bearing testament to their age and history.

In contrast, new beads, untouched by time and wear, have a sharper,

mirror-like reflection. Their surfaces are pristine and undisturbed,

which allows them to reflect light directly, creating a bright and

eye-catching shine.

This difference in reflection quality is one of the most reliable ways

to distinguish between ancient and new beads.

|

|

|

|

Ancient bead, worn by generations of human beings

|

Indeed, some dishonest dealers or artisans may attempt

to simulate the natural patina of an ancient bead

through artificial means to deceive buyers or

collectors. Sand-polishing is one such technique.

During the sand-polishing process, beads are placed in a

drum with sand and then tumbled for an extended period.

This abrasive action can wear down the bead's surface

and create a soft shine, mimicking the patina that

develops naturally over centuries of human contact.

However, while this method may produce a superficially

similar appearance, it generally can't replicate the

depth and subtlety of the patina found on genuinely

ancient beads. This artificial patina often lacks the

unique character and unevenness that result from the

countless human interactions ancient beads have endured.

Furthermore, sand-polished beads may exhibit tiny,

uniformly distributed scratches under a microscope, a

sign that is typically absent in genuine ancient beads.

The practice of artificially aging beads is considered

unethical in many circles, especially when done with the

intent to deceive. As such, collectors and enthusiasts

are encouraged to scrutinize beads closely, ideally with

the help of a magnifying glass or microscope, to detect

any signs of artificial aging. It's also crucial to

purchase from reputable sources to avoid inadvertently

buying artificially aged or counterfeit beads.

|

|

|

|

Fake

bead

|

It is quite obvious that the bead above is a fake. Even this

photo can show it.

However,

counterfeit or imitation ancient beads can be quite convincing, and this

has become an increasing challenge for both collectors and experts

alike. Advances in technology and craftsmanship have made it possible to

create fakes that are very similar in appearance to their authentic

counterparts.

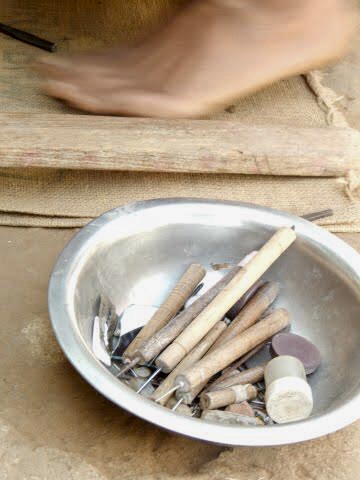

THE SWEAT OF HUMAN EFFORT

We now shift our focus to

the intricate process of stone bead creation. In the

early stages of bead making, bead production was a

laborious, time-consuming task. Consequently, a finely

crafted bead was a rarity and often reserved for the

elite strata of society. But with the advent of new bead

production technologies such as the polishing bag and

diamond drill, stone beads became more commonplace. They

embarked on a societal journey, transitioning from

exclusive symbols of the upper echelons to more

widespread adornments, finally finding their place

within the poorer communities. Today, the age-old

tradition of stone bead making and the search for raw

agate is upheld by the Bhils (or Bheels), using the

simplest of tools.

The Bhils are indigenous to India, known as the largest

tribal community in the country. Revered by Gandhi as

the Adivasis, or the 'original inhabitants', they

represent the primordial roots of the region.

The Bhils' ancestry can be traced back to the original

Indus Valley civilization, pre-dating the Vedic-Aryan

settlement. One might argue that the Bhils and their

beads embarked on a social detour, transitioning from

the splendor of one of the world's most affluent and

enigmatic ancient cultures to their current position as

outcasts, marginalized and stigmatized by their newer

Vedic overlords. As alluded to elsewhere on

ancientbead.com, there is likely a

connection between

the Buddhist affinity for stone beads and the

similar sentiment shared by the earlier Indus

civilization.

THE DIVERSITY OF MATERIALS UTILIZED IN BEAD MANUFACTURE

Beads have historically been fashioned from a wide variety of materials,

including glass, bone, ivory, wood, and even seeds such as the revered

Rudraksha.

Metals like gold, silver, and bronze have also been used to create

beads. Their intrinsic value, malleability, and luster have made them a

preferred choice for creating high-status and ceremonial beads.

Lastly, ceramics and clay have been used extensively for bead-making due

to their availability and versatility. From simple fired clay beads to

intricately decorated ceramic beads, these materials provided an easily

accessible medium for bead artisans throughout history.

Beads made out of stone

Nevertheless, the primary focus at Ancientbead.com lies with stone

beads.

During the ancient era of the Indus Valley civilization, bead artisans

pursued extraordinary lengths to obtain unique and unusual stone

materials. As a result, we encounter numerous

beads crafted from fossilized stones

hailing from this period.

Since the Indus period the range of stones used in bead creation has

been remarkably broad, and their classification can often seem

perplexing and inconsistent. The subjective lens through which a

geologist, mineralogist, gemologist, and archaeologist view and

interpret a specific stone type can vary significantly, underscoring the

inherent complexity and ambiguity present in this field.

Microcrystalline Silicates

Nonetheless, agate, chalcedony, carnelian, chert, flint,

jasper, chrysoprase, sard, and onyx collectively

constitute a category of closely related, yet remarkably

diverse, sedimentary rocks known as microcrystalline

silicates. These materials are predominantly composed of

microscopic quartz crystals formed by the chemical

precipitation of silica from an aqueous solution.

Despite their mineralogical similarity, microcrystalline

silicates exhibit a high degree of visual diversity that

resists easy or definitive classification. They range

from entirely opaque to semi-translucent, may exhibit a

monochromatic or variegated palette, and can display an

array of unique patterns and banding. Thus, this

fascinating group of stones offers a virtually limitless

selection of textures and hues, providing ample creative

fodder for the discerning bead crafter.

DIAPHANEITY:

Light Interaction with Minerals

One key characteristic of minerals that's particularly

important in bead making and gemology is diaphaneity.

This term describes the way light interacts with a

mineral's surface and passes through it.

Transparent: If light can pass through a

substance undisturbed, without any distortion, the

substance is considered to be transparent. This quality

allows you to clearly see through the mineral. Gemstones

like diamond, amethyst, and quartz are examples of

transparent minerals.

Translucent: If light is able to pass through a

substance, but in a distorted or diffused manner, such

that objects cannot be clearly discerned through it, the

substance is considered to be translucent. Many types of

agate and some forms of jade and carnelian are typically

translucent.

Opaque: If light cannot pass through a substance

at all, it is classified as opaque. These materials

absorb or reflect all light that strikes them, and no

light passes through them. Examples of opaque minerals

commonly used in bead making include lapis lazuli,

turquoise, and most types of jasper.

The degree of diaphaneity can greatly affect the

appearance and aesthetic appeal of a bead or gemstone,

influencing factors such as color intensity, depth, and

perceived 'glow' or 'fire' within the stone. Thus,

understanding diaphaneity is crucial for both

gemologists and bead artisans.

MINING AND COLLECTING

OF RAW MATERIAL

The sourcing of raw materials for bead making is a

critical step in the process, and traditionally the

ideal location for a bead manufacturing site would be

one with easy access to these materials as well as a

nearby market for selling the finished products.

Historically, Gujarat in India has been a major hub for

this activity, providing abundant access to high-quality

materials ideal for bead creation.

The ancient mines of Baba Ghori in Ratanpur, Gujarat are

a notable example. These mines are dug 30 to 35 feet

deep until the layers of carnelian or agate are reached.

The blocks of stone that are mined, weighing one to two

pounds, are brought to the surface and chipped right at

the mining site. From there the stone are transported to

the nearby city, Cambey.

However, the ancient history of bead making did not origin in Cambey. It

began in the nearby ancient site Harappan,

Lothal.

Interestingly, in Lothal

we find the world's earliest known dock, which connected the city to the

Sabarmati river. Seen in this context it gives meaning that we find

Indus beads as far away

as Troy.

Even today, the

Bheel community continues the tradition

of 'hunting' for stones in the major mines of Gujarat.

These mining locations and the traditions associated

with them date back to the times of the Indus Valley

civilization, making them several thousand years old!

Outside Gujarat

We must not forget that there there were (and are) a number of other

locations where minerals suitable for bead-making were procured.

Afghanistan, in particular, is a country rich in mineral resources, many

of which were historically used for bead production.

Lapis Lazuli: Perhaps the most famous mineral exported from Afghanistan

for bead-making is lapis lazuli. This vibrant blue stone has been prized

for thousands of years and was a key part of the ancient trade networks

extending as far west as Egypt and as far east as India. The

Sar-e-Sang

mine in Afghanistan's Badakhshan province has been a primary source of

lapis lazuli for millennia.

Carnelian: This semi-precious gemstone, also known as cornelian, is a

reddish variety of chalcedony that's been used for bead-making for

thousands of years. It was often sourced from the regions that are now

Afghanistan and Pakistan.

Other Gemstones: Afghanistan is also known for its deposits of emeralds,

rubies, garnets, and other precious and semi-precious stones, all of

which have been used in jewelry and bead-making.

We also have to mention the other important bead procurement places

along the silk route in ancient times.

Egypt: Egypt is home to several ancient mines and quarries. Malachite

and turquoise were extracted in the Sinai Peninsula, and carnelian was

sourced from the Eastern Desert.

Mesopotamia (Present-day Iraq): The ancient civilizations in this

region, like the Sumerians and Akkadians, traded for carnelian, lapis

lazuli, and other semi-precious stones for bead-making.

Persia (Present-day Iran): Ancient Persia was a rich source of

turquoise, a stone that has been used for millennia in jewelry and

bead-making.

Greece: The island of Crete in Greece was renowned for its gold, silver,

and lapis lazuli, which were used in the creation of Minoan beads.

Minoan seals are among the finest ever made.

Historically, expansive trade networks such as the Silk Road connected

disparate regions, facilitating the exchange of diverse goods including

raw materials, finished beads, and other commodities. For instance,

beads crafted in Afghanistan could incorporate materials sourced from

far-off lands, and conversely, Afghan materials could be found in beads

produced elsewhere. In this way beads were travelling, even before

they became beads.

Methods for

Obtaining Raw Materials

Finding the perfect stone for bead making isn't easy.

These mining sites often contain a significant amount of

debris, including flakes of stone and stones that have

cracked in unfavorable ways. These discarded materials

form a sort of 'bead junkyard' that can be thousands of

years old. However, nothing is wasted; smaller beads can

often be made from these discarded pieces, recycling

what might have been seen as waste into valuable

products. This practice of reusing and repurposing

materials is not a modern invention, but an ancient

tradition that has been carried forward into the present

day.

There have been various techniques employed over the

ages to source stones for bead-making. One of the most

common was to look for them in eroding cliffs or rocky

outcrops. The action of wind and water often exposed

suitable stones, which could be readily collected.

Another method involved a more proactive approach. A

fire would be built near a cliff face, heating the stone

surface. Cold water would then be thrown onto the heated

cliff, causing the abrupt temperature change to induce

cracking and flaking in the stone surface. This could

effectively 'harvest' stone from the cliff in a

controlled manner.

Searching in river beds was yet another method. River

water, particularly in fast-flowing streams, has a

tendency to erode and polish stones, leading to the

natural production of semi-finished stones suitable for

bead-making.

Once the stones were collected, flakes were struck from

the nodules to assess the quality of the stone. The best

pieces of agate were then left in the sun for a period

of time - often several months - to draw out any

remaining moisture in the stone.

Following this natural drying process, selected stones

were subjected to further artificial heat treatments. As

discussed in the

Sulemani bead chapter, different

heating techniques

were used to produce different types of beads. The first

heat treatment after sun drying was usually carried out

in terracotta vessels or simple pit kilns and was aimed

at removing any residual moisture. This process made it

easier to flake the stones, as moisture within the

stones could lead to unpredictable flaking patterns.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Unearthed at

archaeological sites, these rough-outs share striking

similarities with those we might find today in the

bustling bead industry of Cambay, located in Gujarat,

India. Their shape and markings point towards the

ancient practice of hand-sawing and chipping raw stones

into shape. The traditional method, termed inverse,

indirect percussion (Kenoyer, 1986), was a meticulous

art passed down through generations.

This labor-intensive technique required a stake, usually

made from iron or other sturdy materials, to be firmly

planted into the ground at an angle of approximately 45

degrees. The artisan would position himself on the

ground, steadying the stake with one knee. The rough

stone was held in the left hand while the right hand was

tasked with gently hitting the stone against the stake.

This careful percussion allowed the artisan to chip off

minute flakes without fracturing the entire stone,

requiring around 3 to 4 hours of painstaking effort to

shape a single bead.

Before the advent of iron tools, copper was commonly

used for the stake, and even earlier, deer antlers may

have served the same purpose. The distinctive signs of

flaking resulting from this shaping process are easily

identifiable and unique to handcrafted beads.

Today, while some aspects of this age-old craft persist,

many elements have undergone a shift in response to

technological advancements. Most notably, the cutting of

stones is frequently performed using electric-powered

saws, a far cry from the hand tools of yesteryears.

DESIGN

& SHAPE

The

design and form of ancient stone beads often seem to

have been influenced by the inherent patterns and

characteristics of the raw material itself. This

suggests that even at the stage of mining, the workers

were on the lookout for distinct stone patterns that

could eventually serve as a central motif in an

exceptional bead. As a result, the natural beauty of the

stone patterns was recognized and celebrated by their

makers from the very outset of the process.

The Pursuit for the Exceptional Bead Amidst Urban

Expansion

During ancient times, particularly amongst the Indus

Valley civilizations, artisans went to great lengths to

procure exotic stones to create beads of varying colors,

shapes, and sizes. This effort escalated towards the end

of the Indus culture and the beginning of the Classical

period, around the first millennium B.C., coinciding

with India's Urban Revolution on the Gangetic Plains.

This transformative era ushered in a demand for

distinctive beads that could act as artistic reflections

of the burgeoning self-consciousness accompanying city

life. As society transitioned from pastoral and agrarian

ways to a more urbanized lifestyle, the representation

of status, power, and individuality through personal

adornments became more significant.

During this period, bead making came under the patronage

of kings, priests, and merchants, causing it to flourish

amidst a rich cultural tapestry of patterns, colors, and

exotic materials. The bead, thus, not only served as a

simple decorative object but also a symbol of

socio-cultural evolution, mirroring the changing

dynamics of society.

The outstanding bead displayed below

from Rakhigarhi is an example of this hunt for the urban exotic

and rare:

|

|

|

|

|

Beads are indeed

crafted in a wide array of shapes, largely constrained

by the available technology and the characteristics of

the raw material. At one end of the spectrum, we find

beads that are essentially naturally occurring stones

that have been smoothed through tumbling and

subsequently pierced to create a hole:

|

|

|

|

|

Exceptional beads often demonstrate a high degree of

artistic intelligence and skill in their creation, as is

evident in the magnificent crystal tiger bead depicted

below:

|

|

|

|

|

This bead stands as a testament to the craftsman's

expertise and artistic vision. It demonstrates not only

a mastery of technical skills but also a deep

understanding of aesthetics, symmetry, and design.

The process of crafting such a bead involves more than

just selecting the right stone. It requires meticulous

planning, precise execution, and a keen eye for detail.

The artisan has to understand the inherent properties

and limitations of the material, envision the final

product, and carefully manipulate the stone to bring

that vision to life.

The finished bead is a perfect harmony of form, color,

and texture, revealing both the natural beauty of the

crystal and the masterful artistry of its creator. Such

exceptional pieces transcend their utilitarian purpose

as beads and enter the realm of fine art.

In very rare cases the artisans were composing beads through the process of cementing different types of stones with different patterns together:

|

|

|

|

15 * 6,5 mm

Click on picture for larger version

|

The bead showcased below is an

example of a counterfeit bead I came across during my time in Burma as a

tour guide. Local villagers would bring these types of beads to sell to

unsuspecting tourists. Intriguingly, it is a composite piece, glued

together from various parts. Notably, only the carnelian segments are

derived from original ancient beads that were broken. I somehow still

adore this semi-original bead and believe it was worth every penny I

paid for it.

|

|

|

|

|

How to

liberate the dormant beauty in a stone

As previously mentioned, the inherent pattern or motif within a stone

often dictates the form the bead will take, and in turn, this form

accentuates the motif. A keen eye for aesthetics, understanding of

symmetry, and careful consideration of the stone's natural patterns are

essential in this process.

|

|

|

|

21 * 19 * 13 * 6 mm

|

Take, for

instance, the

Indus Valley bead displayed above. Notice how the

symmetry inherent in the stone has guided the crafting

of the bead. The artisan, working with the natural

design rather than against it, has highlighted and

emphasized its inherent beauty. This interplay between

nature's artwork and human craftsmanship is what

elevates these beads from simple ornaments to true works

of art.

Consider the small bead displayed below. In it, we see a

prime example of this synergy between the natural beauty

of the stone and the artisan's handiwork. The artisan

has not merely shaped the stone but has unleashed its

dormant aesthetic potential, allowing it to reveal its

true beauty to the world. Its an organic process,

almost as if the stone and artisan are in conversation,

ultimately resulting in a piece of art that is as much a

testament to the nature of the material as it is to the

skill of the bead-maker.

|

|

|

|

11 * 10 * 3 mm

|

The Golden Angle

in Motifs: A Case Study from the Indus Valley

The golden

angle is a

mathematical concept found frequently in nature and used widely in art

and design. This angle, approximately 137.5 degrees, is derived from the

golden ratio, a mathematical constant found in many aspects of life,

from the spiraling pattern of a nautilus shell to the branching of

trees.

This principle extends to bead-making as well. In many ancient bead

designs, the golden angle can be found. A fine example of this can be

seen in the Indus Valley bead illustrated below.

|

|

|

|

17 * 14 * 4 mm

|

Observe the

motifs and how they reflect this golden angle. The

artisan behind this bead, consciously or subconsciously,

has used the principles of sacred geometry to create a

design that is visually harmonious and balanced. This

adherence to the golden angle, whether intentional or

not, gives the bead a timeless aesthetic quality,

connecting it to the universal patterns found in nature

and art.

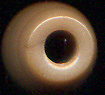

In the

Magic Eye

Bead below the eye is placed in the symmetric

middle:

|

|

|

|

28 * 19 mm

|

Or it can be placed in the golden angle position:

|

|

|

|

24 * 10 mm

|

|

Adopting Human Body Forms in Bead Design: An Exemplar

Agate Bead

The fusion of art, utility, and anthropology is an intrinsic

part of bead making, where artisans have traditionally kept in

mind not just the aesthetic appeal but also the comfort and fit

of the bead when worn. One such outstanding illustration of this

thoughtful craftsmanship is seen in the long agate bead

displayed below, crafted with a specific consideration for the

wearer's body shape.

|

|

|

|

83 * 12 * 8 mm

|

This agate bead is expertly shaped and polished to

feature a flat, bow-like side. This unique design allows

the bead to comfortably contour to the curves of the

human body when worn. This kind of thoughtful design is

part of what makes ancient beads so fascinating. The

artisan who crafted this piece centuries ago was not

merely creating an adornment, but a piece of wearable

art designed with the wearer's comfort in mind.

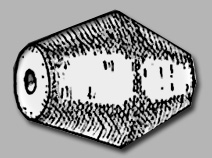

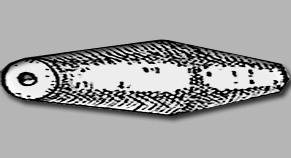

ARCHETYPICAL

BEAD SHAPES

Below you will find

illustrations of a few of the most typical bead forms.

|

|

|

|

Bicone

|

Long Bicone

|

Hexagonal Tube |

Round Tube

|

Barrel |

Collar |

Cylinder /

Lenticular |

Round tabular |

Mellon

|

Ball

|

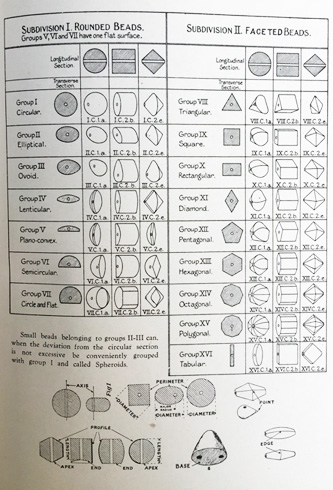

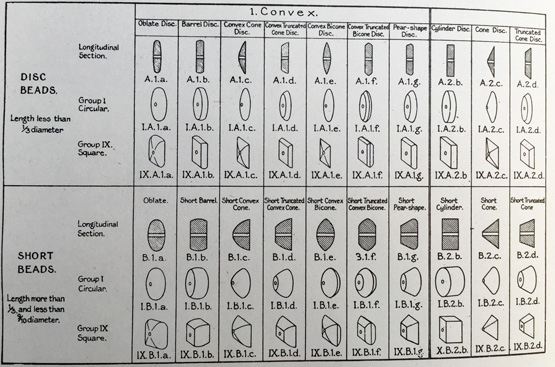

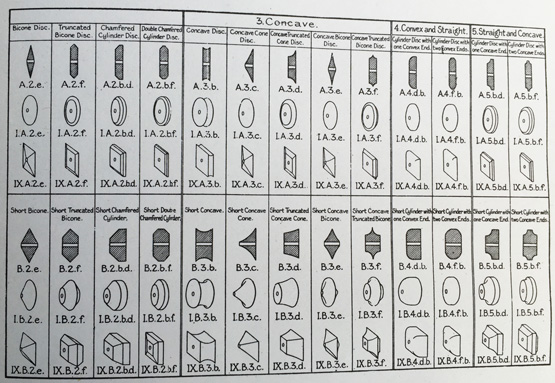

Here you will find more detailed illustrations of bead forms

borrowed from the book, The beads from Taxila, by Horace Beck

|

|

|

|

Click on

pictures for larger versions

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Click on

pictures for larger versions

|

THE

GRINDING & POLISHING PROCESS

Crafting beads is a

multifaceted process, with distinct stages of

development entrusted to specific artisans. The miners

who unearthed the raw agate from the ground were

different from those who chipped and rough-shaped the

beads, who were in turn distinct from those responsible

for the final grinding and polishing.

|

|

|

|

Hand grinding of beads

Neolithic hand grinding stone

|

Historically, many

beads were prone to breakage during the complex

drilling process.

As such, the bead's polishing was often reserved until after a

successful drilling operation.

In ancient times, this polishing process was laboriously conducted by

hand. It involved a succession of different grinders, starting with

siltstone or quartzite for the initial rough polishing and culminating

with a smooth wooden surface for the final finish. The artisans used

progressively finer abrasives - like agate dust or other suitable

materials - to bring the bead to its final form.

This meticulous hand-polishing could take an extraordinary amount of

time. For instance, grinding a single large bead could take up to five

days in ancient times. Today, with the aid of modern machinery, the same

process can be accomplished in a mere five minutes.

Interestingly, the surface texture of a bead can reveal insights into

the polishing techniques used. For instance, the uneven surface of the Indus Valley bead

pictured above indicates a polishing technique that used very rough

abrasives. This evidence of the artisan's hand, preserved in the bead's

surface, adds another layer of depth to its history and appeal.

|

|

|

|

21 * 8 * 6,5 mm

|

ROCK POLISHING TECHNIQUES IN

ANTIQUITY

In ancient Egypt, the art of

rock polishing was painstakingly performed by slaves. Stones, carefully

chosen for their qualities, were manually chipped into initial shapes.

The subsequent process involved placing these stones into troughs filled

with a combination of sand and water. Through a repetitive

back-and-forth movement in these troughs, the stones gradually became

smoother, eventually achieving a polished finish. This "tumbling"

technique, albeit effective, was extremely time-consuming. It was not

uncommon for the polishing of a single stone to span several months.

Bag Polishing - Revolution of Tumbling in Ancient India

A remarkable advancement in bead polishing was introduced in ancient

India with the development of a new technique known as tumbling, also

referred to as bag polishing. Prior to this innovation, each bead was

individually shaped and polished, either by hand-rubbing or employing a

somewhat mysterious Persian method.

The advent of bag polishing allowed for the simultaneous polishing of

multiple beads. Artisans would place a number of beads into a goatskin

bag, along with water and dust from agate or jasper. Then, two

individuals would roll the bag back and forth on the ground over a

course of several days, even weeks. The resulting movement and the

abrasiveness of the dust within the bag effectively polished the beads.

|

|

|

|

|

|

This ingenious tumbling method, in conjunction with the

second-century BC invention of the diamond drill, laid

the foundation for the mass production of beads.

However, the shift towards efficiency in mass production

often came at the cost of individual craftsmanship and

personal touch. The societal, economic, and

technological changes of the time were reflected in this

transition to bag polishing.

The precise origins of the bag polishing technique for

stone beads remain a subject of speculation. It is

believed to have likely been developed during the late

first millennium BCE, with its usage becoming more

widespread during the early Common Era, in line with the

emergence of large-scale bead production.

These timelines, however, are largely drawn from

archaeological evidence and historical contexts, and may

vary across different regions or cultures. It's also

worth noting that different civilizations may have

independently developed similar techniques at varying

times.

Technological advancements, like bag polishing, rarely

occur as singular "eureka" moments. Instead, they

typically evolve and improve over time. Techniques like

bag polishing would have likely undergone numerous

refinements and adaptations over generations, gaining

popularity as their effectiveness was proven.

|

|

|

|

55 * 13 mm

|

The large red Jasper bead

shown above, with its relatively large hole, appears to

originate from the Indus period, given its similarities

to beads from early Indus sites in present-day

Baluchistan. Interestingly, the bead exhibits evidence

of having been polished in a tumbler, suggesting that

the technique of bag polishing might have been known

even during the time of the Indus civilization.

In this particular instance, the bead maker appears to

have let the tumbling process dictate the shape of the

bead. The uneven design and lack of deliberate artistic

shaping suggest minimal manual intervention, which could

indicate a rudimentary level of craftsmanship. This

might hint at a dual-tier bead-making industry during

the Indus period: one that utilized bag polishing to

mass-produce simpler, lower-cost beads for the lower

classes, and another that used more labor-intensive

hand-polishing techniques to create high-quality beads

for the upper echelons of society.

|

|

|

|

|

The bead shown above

exhibits a characteristic 'tumbled design'. Notice the

gentle curves and soft corners of the bead; these are

distinctive traits resulting from bag polishing. This

method, while efficient for mass production, tends to

limit the variety of bead forms that can be achieved.

Thus, the cost of mass production is often a degree of

monotony and uniformity in bead shapes.

In contrast, the bead displayed below has not undergone

the tumbling process. It has sharper edges and likely

reflects a more intricate and personalized crafting

process. Its design and form represent the wider range

of possibilities that come with handcrafted techniques,

highlighting the unique character inherent in

individually made pieces.

|

|

|

|

17 * 11 mm

|

The time-consuming process of hand rubbing the beads had one advantage that was lost with the bag polishing: The hand shaped beads can display edges and sharp designs like you can see in the beads displayed below:

|

|

|

|

12 * 11 mm

|

|

The same is the case with Zoomorphic, human and other distinctive designed beads; they would lose their shape in a tumbler.

|

|

|

|

23 * 8 * 4 mm

Ancient carnelian roman/greek sword bead

|

Of course, the hand-polishing of beads did not disappear. However, the hand-polished beads got great competition from the mass producing 'new' tumble technique.

Here you can see a multi-faceted carnelian bead from the British period:

|

|

|

|

11 mm

|

The sublime Mauryan bead

polishing

The

Mauryan period marked an unprecedented pinnacle in

bead polishing, wherein artisans seemed to apply

extraordinary, now lost, techniques that paralleled

those used on Mauryan pottery and monuments. This

supposition, while still a hypothesis, is based on the

remarkably fine finish observed on Mauryan beads, as

exemplified by the one shown below.

|

|

|

|

Banded

Buddha

|

The Mauryan polish on agate and carnelian beads is

perhaps unrivaled in any other period in history. We

have no independent evidence as to how this polish was

imparted on the beads, but it probably was not far from

the one used in polishing the famous pillars on which

the edicts (of Ashoka) were carved...

(Indian Beads - Shantaram B. Deo p.14)

|

|

|

|

Ashoka's four lions - Museum in Sarnath

These Ashoka Lions were erected on 15 meter

tall pillars everywhere in Ashoka's vast Empire.

|

Today, it is widely believed that the exquisite

sandstone lions exhibited above were most likely crafted

by Persian artisans. Their style, as noted in the

museum's text, appears distinctively Persian. The unique

polishing technique displayed also seems to be of

Persian origin. The Mauryan capital,

Pataliputra, appears to have emulated Persepolis,

the ceremonial capital of the Achaemenid Empire in

Persia.

It's conceivable that the rise of the Mauryan Empire was

underpinned by alliances formed between residual Persian

military units left in disarray after Alexander the

Great's conquest and subsequent destruction of the

Persian Empire and insurgent factions within Indian

society. Notably,

Chandragupta Maurya, the founder of the Mauryan

Empire, was a person of lower caste who forged a

powerful alliance with the renowned Brahmin scholar,

Chanakya.

In this light, the emergence of the first super culture

following the decline of the expansive Indus

Civilization appears to have been sparked by the

remnants of cultural destruction left by Alexander the

Great's conquests. The Mauryan Empire, it seems, was

built upon the cultural rubble of Persia, amalgamating

the finest elements of both Persian and Indian cultures

to form a dynamic synthesis.

This historical conjecture becomes particularly

intriguing in the context of bead-making, given the

convergence of Persian's supreme (and now lost)

polishing techniques with India's established

bead-making traditions. The result was an extraordinary

blend of craftsmanship that echoed the cultural synergy

of the era.

HEAT TREATMENT IN BEAD MAKING

The enigmatic Indus Valley civilization deserves

commendation for their innovative techniques in

enhancing the color of agate through heat treatment

techniques still employed today in Cambay, Gujarat. This

heating process is done in multiple stages, following

the initial drying and heating processes described in

the 'Mining and Collecting of Raw Material' chapter. It

typically takes place after the bead has been roughly

shaped and the hole has been drilled.

In this process, beads are sorted based on design,

color, and potential color changes, and are then placed

into various clay pots. These pots are then positioned

within small, low-walled brick enclosures. Surrounding

the pots, a combination of ashes and cow or goat dung is

carefully layered. Simultaneous ignition is crucial to

prevent thermal shock.

The agate is gradually heated to a temperature around

340 degrees Celsius, with cooling also conducted slowly

to prevent unwanted cracks in the stones. Even so, the

process is not foolproof, and unwanted cracks can still

occur during a perfectly executed heating process.

This procedure, therefore, requires the supervision of a

highly skilled craftsman, trained in this craft by his

father, often part of an unbroken generational chain

stretching back to ancient times. It is no surprise that

father's name is an essential detail in an Indian visa

application, symbolizing the cultural importance of

lineage and continuity. The intricate art of bead

making, handed down through generations, is a testament

to the enduring brilliance of these ancient practices.

Distinguishing Between

Cooked or uncooked agate beads

When it comes to agate

bead treatment, not all stones undergo the heating

process. After extraction, the agate is typically

separated into two categories: stones that would benefit

from heat treatment for color enhancement, and those

that naturally display a beautiful, translucent shine

without the need for heating.

For the latter group, their intrinsic allure is left

untouched, allowing the original hues and features of

the agate to shine through in the final product. An

example of this 'uncooked' bead can be seen below. Such

agate beads, that are not subject to heat treatment, are

often referred to as 'uncooked,' preserving their raw,

authentic beauty.

|

|

|

|

17 * 14 * 6 mm

|

Heat Transformatin:

From agate to carnelian

A particularly remarkable

feature of certain agate stones, specifically those

originating from Cambay in India, is their capacity to

transform into carnelian under the influence of heat.

The characteristic reddish-orange color of Carnelian, a

prized attribute of this semiprecious stone, can be seen

in the example below:

|

|

|

|

Cambey carnelian

|

|

The transformation of the grayish agate to the radiant

carnelian is largely due to the high iron oxide content

within the stone. When subjected to heat, the rusty iron

oxide imparts a warm, reddish hue to the agate.

The uniformity of the resulting coloration depends on

the consistency of porosity and iron concentration

within the agate. Heat exposure transmutes the agate

into a beautifully rich brownish or reddish-orange

stone.

Agates with

relatively uniform porosity tend to exhibit consistent

coloration post-enhancement. Nonetheless, the color

uniformity of carnelian also relies on the consistent

concentration of iron throughout the stone. From

archaeological findings, it seems that the ancient Indus

people favored non-translucent, almost opaque

carnelian beads

with even coloring, similar to the bead seen here:

|

|

|

|

27 * 9 mm

|

Achieving the Ideal

Carnelian Color

The process of transforming agate into carnelian

often required multiple rounds of careful heating,

sometimes up to ten iterations, in order to achieve the

desired deep red color, which was considered top

quality. You can observe this rich hue in the carnelian

beads

displayed at this link.

The history of carnelian production

This invention of transforming gray agate into carnelian is

ancient. We can find heat treated carnelian as far back as the Neolithic period:

|

|

|

|

Neolithic disk bead from Sahara, Africa

|

Here in these very

Early Indus Valley beads we can observe a beautiful blood like

the color of carnelian:

|

|

|

|

|

As we journey back in time,

the line between rational thinking and magic becomes

increasingly blurred. The significance of carnelian

beads to the Indus people remains largely unknown, but

historical texts from Mesopotamia, a civilization

contemporaneous to the Indus Valley, suggest a magical

aspect to these gemstones. The deep red color of

carnelian was believed to be associated with

purification of the blood and overall health, revealing

an early understanding of the concept of healing stones

and their potential metaphysical properties.

Understanding

Agate and Onyx

Agate is distinguished by

its irregular, curved bands of various colors, formed

layer by layer in volcanic rock. Onyx, another variety

of chalcedony like agate, has straight, parallel bands,

often in black, white, or shades of brown. These

distinct banding patterns are a result of their unique

geological formation processes.

|

|

|

|

Fine

circular banded Onyx and Sardonyx versus agate:

|

A particular variety of

onyx, characterized by its carnelian iron color banding, is

known as Sardonyx.

However, the nomenclature around various

microcrystalline

silicates can be somewhat confusing.

Sardonyx

originally referred to a specific stone found in

Sardinia. Today, however, agate that has been colored to

resemble carnelian and features fine circular banding is

often termed as Sardonyx.

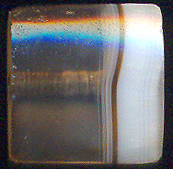

Below you can enjoy two

stunning translucent sardonyx beads, or should we just

call it fine banded agate or onyx beads?

|

|

|

|

34 * 8 mm

Click on picture for larger version

|

|

|

|

25 * 6 mm

|

|

|

|

Bhaisayayguru sulemani bead

|

The intricate process that transforms an ordinary agate

into what is widely referred to as a

Sulemani agate bead

in India and the far East, likely dates back to over

four thousand years ago, credited to the inventive

prowess of the Indus Valley civilization. Naturally

occurring banded brown/black and white agate is quite

rare. Typically, agate in its unprocessed state exhibits

a whitish or grayish hue, as evident in the

'uncooked' Indus Valley bead

shown below:

|

|

|

|

|

It's plausible that

this bead was

crafted before the advent of heat treatment for beads...

or perhaps the artisans simply preferred the

translucent, whitish glow of this stone. To achieve a

bead similar to the brown and white banded Bhaisayaguru

stone seen in the first picture, Indian craftspeople

started immersing the agate stone in oil, honey, or

sugar water. The sugar is absorbed more readily by the

darker and/or more porous layers, but not by the denser

white layers. During the heating process, the sugar

undergoes caramelization, turning the porous layers into

a deep black or rich brown, as can be observed in the

bead shown below:

|

|

|

|

|

Nevertheless, every innovation carries a trade-off. The

transformation of agate into onyx often compromises the bead's

translucent sheen. Translucent beads with black stripes are a

rarity, possibly explaining why the artisans of the Indus Valley

chose not to treat certain beads, especially those with

captivating translucent bands and white stripes. An exemplary

bead of this kind can be observed below:

|

|

|

|

|

The alteration with

sulphoric acid

Over 2000 years ago, bead artisans refined their

techniques even further. They found that submerging a

sugar-soaked stone in sulphuric acid led to the

carbonization of the sugar, creating a striking black

hue instead of brown. Frequently, the artisans would

further augment this artificially enhanced banding

through a technique that deprived the stone of oxygen

during the heating process. The resulting onyx bead, a

magnificent opaque black agate, can be seen below. Also,

take note of the white banding visible in areas where

the stone's density prevents the chemicals from

permeating. These dense sections retain their natural

color, providing a stark contrast to the induced black

hues and adding a distinctive pattern to the bead.

|

|

|

|

|

During this era, Buddhism was predominant in India.

Perhaps this is why the brown or black Sulemani onyx

bead remains the most coveted prayer bead for Buddhists

worldwide, even today. For more information on the heat

treatment process of beads, please refer to the

Sulemani Beads section.

THE ETCHING OF BEADS

The intricate design

adorning the ancient bead displayed below was

meticulously crafted using an alkali soda-based process

known as

etching. Etching is mostly done on carnelian

beads.

|

|

|

|

EB 1 - 12,5 * 4,9 mm

|

Etching on

carnelian beads is a fascinating process that involves

the careful manipulation of the stone's surface to

create intricate designs and patterns. While the exact

techniques may have varied among different cultures and

eras, the general principles of the process remain

consistent.

Preparation:

The bead begins as a rough piece of carnelian that has

been shaped into the desired form. Carnelian, a variety

of chalcedony, is chosen for its hardness, beautiful

color, and ability to hold intricate etched designs.

Design Mapping:

Once the bead has been shaped and smoothed, the artisan

outlines the design onto the bead using a sharp tool.

This stage requires precision and an understanding of

how the design will ultimately look on the rounded

surface of the bead.

Etching:

The outlined bead is then treated with a solution often

consisting of an alkaline soda. This could be a

naturally occurring substance, such as plant ash or

natron, which was used in ancient times. The solution is

applied only to the areas of the bead that are to be

etched. This solution selectively erodes the surface of

the carnelian, carving the design into the bead.

Heating:

The bead is then heated to intensify the color contrast

between the etched and unetched areas. The heat causes

the etched areas to turn white, while the rest of the

bead retains its rich carnelian color. This temperature

treatment also serves to enhance the durability of the

etching.

Polishing:

Finally, the bead is carefully polished. This can smooth

out any roughness from the etching process and adds a

beautiful shine, making the etched design stand out even

more.

|

|

|

|

EB 1 - 13 * 11 * 5 mm

- Indus Valley etching

|

This unique decorative method has roots stretching back

to the Indus Valley and Harappan Civilizations around

2500 to 1500 BC. The Mauryan Period, under the

leadership of Chandragupta Maurya from 300 BC to 100 AD,

is recognized as the epoch when the craft of etching

beads reached its zenith in terms of quantity.

From 274 BC onward, India was under the benevolent reign

of Ashoka the Great, Chandragupta Maurya's grandson,

during which Buddhism became the predominant philosophy.

This historical context is crucial, as even today,

etched beads retain a special place in the hearts of

Buddhists around the world. Their historical and

spiritual significance, coupled with their aesthetic

appeal, ensures their enduring popularity.

|

|

|

|

EB 3 -

12 * 4,5 mm

This bead is actually not etched,

but displays natural lines in

jasper stone.

|

|

|

|

|

The image

above showcases an Indus Valley bead, remarkable in its

original, untouched pattern. Conversely, the bead

depicted below has been artificially colored to echo the

natural patterns found in its Indus predecessor. This

practice of etching beads emerged from a desire to

create visually stunning designs that might be otherwise

difficult or time-consuming to locate within the natural

patterns of the stones. Instead of painstakingly

searching for stones with inherent, appealing patterns,

artisans found a shortcut: enhancing the banding or

etching patterns directly onto the beads. This

innovative etching technology was birthed during the

Indus Valley era.

|

|

|

|

17 * 5 mm

|

Pictured above is a perfect and unique translucent

agate, showcasing natural banding from the Indus Valley

Civilization, dating back to 3000-1500 B.C. This

precious artifact was unearthed in 1942 in

Harappa,

now present-day Pakistan.

Upon comparing it with the etched bead depicted below,

it's striking to consider that the market value of this

etched 'replica' most probably surpasses that of the

original, un-etched Indus bead. I have personally no

doubt what bead I prefer!

|

|

|

|

|

However, the craft of

etching evolved beyond merely replicating natural

patterns. Over time, artisans began to create symbolic

and religious motifs, expressing intricate narratives

and meanings that surpassed the limitations of naturally

occurring stone patterns.

|

|

|

|

|

Even

in ancient times, these etched beads rose to the

pinnacle of popularity. They were traded extensively

across the ancient world. Frequently, the techniques of

color alteration and etching were combined, as

exemplified in the etched black spherical bead shown

below:

|

|

|

|

|

In rare cases we also find

etching with black lines.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Drilling the hole in a bead is a pivotal

phase in the bead-making process and significantly aids

in its identification and classification. The drilling

process stands as a decisive 'make or break' moment,

considering the inherent risk of shattering the bead

during this delicate operation. Evidence of failed

attempts can be found scattered around ancient artisans'

workshops, testament to the challenges this task

presented.

Due to the potential catastrophe of ruining a fully

polished bead - a laborious effort possibly spanning a

month - the bead hole was drilled shortly after creating

the rough outline of the bead. This strategic sequence

minimized the risk of wasting significant time and

effort on a bead that would subsequently fracture during

drilling.

Creating the hole in a bead was a methodical process,

usually undertaken with careful consideration for the

bead's integrity. To prevent damaging the bead's ends or

'apices', holes were typically drilled from both sides,

as shown in the example below. This approach ensured a

cleaner finish and significantly reduced the chances of

causing a crack at either end of the bead.

HISTORY OF BEAD HOLE

CREATION

Neolithic Drilling Techniques

Incredibly, the production of