|

|

NEOLITHIC BEADS: ECHOES FROM AN ANCIENT TIME

Our journey takes us to the fascinating world of Neolithic stone

beads that have been unearthed from ancient settlements in the Moroccan

Sahara, dating back to around 5000 BC and lasting until approximately

1200 AD. These relics not only hold aesthetic appeal but also provide an

intriguing look into our past, and into a time when the Sahara was not

the vast desert we know today.

Around 3000 BC, the Sahara underwent a dramatic transformation from a

lush, green landscape filled with life, to the expansive, arid desert it

is today. However, this was not always the case. Prior to this

transformation, the Sahara experienced an extended wet period that can

be traced back to at least 8000 BC. It was during these wet periods that

the Sahara was home to Neolithic settlements, traces of which can still

be found scattered across the Moroccan Sahara today.

However, it's worth noting that determining the age of these beads is

often a complex process. The Neolithic period, defined by the advent of

farming and marked advancements in tool making, isn't time-bounded the

same way in Africa as it is in other regions of the world. Some could

argue that in certain parts of Africa, a form of Neolithic lifestyle

still persists, blurring the lines of historical demarcation.

In this context, the patina - the change in surface appearance due to

age and exposure - is often the most reliable indicator of a bead's age.

Moreover, the method of production, the Neolithic technique of bead

making, remained in use for an extended period, perhaps even persisting

in some remote areas to this day.

The 12th Century heralded significant changes in this regard. Arab

traders journeying to Africa brought with them advanced drilling tools

and techniques from India, enabling the creation of more sophisticated

beads. Furthermore, these traders didn't just bring new tools and

techniques; they also carried with them beads crafted in India.

In my travels through Morocco, I've encountered a multitude of these

ancient Indian beads, each with its own unique story to tell. This isn't

surprising, given that beads have always been significant cultural

objects and are often among the first items to be exchanged between

different cultures. Wherever there's evidence of cultural exchange, you

can almost be certain that beads were part of the interaction, acting as

diminutive ambassadors of their native cultures. Therefore, whether in

Africa or elsewhere, these Neolithic beads represent not just beautiful

objects of adornment, but also artifacts of historical and cultural

exchange.

|

The beads in

my collection

are now for sale

Inquire

through bead ID

for price

|

|

|

Wonderful citrin beads - 12 * 5 mm - SOLD

|

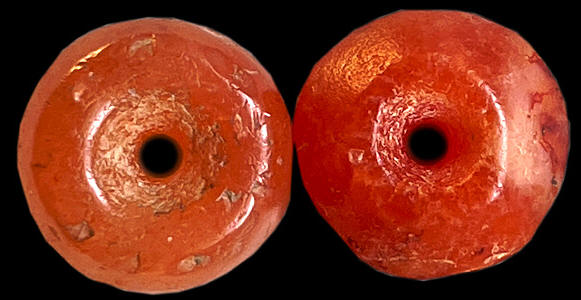

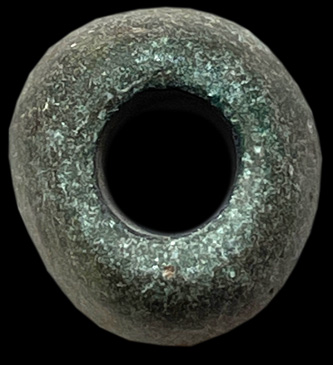

Observe the marked contrast between

the beads exhibited above and those displayed below, despite originating

from the same Neolithic settlements. The upper assortment appears more

rudimentary in shape and craftsmanship when compared to the more refined

ones presented beneath.

There's a plausible explanation for this contrast rooted in the

lifestyle of the communities these artifacts belong to. The societies in

the Sahara during the Neolithic period were primarily comprised of

hunter-gatherers, whose daily survival heavily relied on tools such as

axes, spears, and arrows. The production of these tools, vital for

hunting and defense, may not have necessitated the development of fine

polishing skills, evident in the relatively crude nature of the beads in

the upper display.

In contrast, the lower set of beads, exhibiting a higher degree of

polish and sophistication, are likely to be the product of more settled,

agricultural societies that were emerging during this period. These

communities had more stability and resources to dedicate to

craftsmanship, allowing for the creation of finer, more polished

objects.

There's a tantalizing possibility that these sophisticated beads found

their way to the hunter-gatherer societies of the Sahara through

interactions with these agricultural communities. This could have been

facilitated by contacts and exchanges, perhaps even early forms of

trade. Therefore, these finely crafted beads not only represent an

advancement in craftsmanship but also bear silent testimony to the

burgeoning connections between societies in the Neolithic period.

|

|

|

|

|

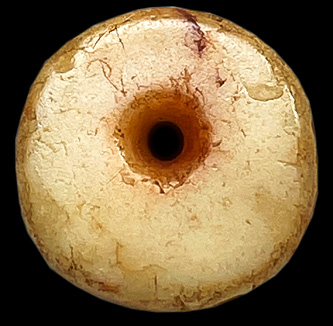

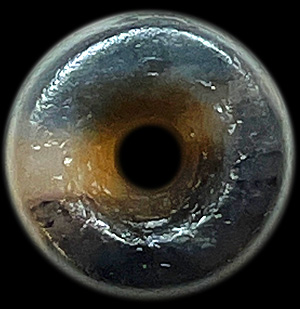

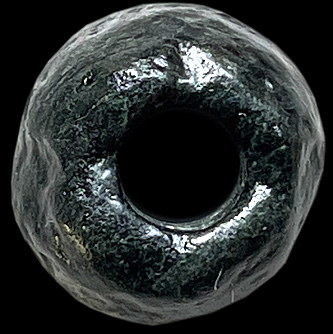

The bead featured above, discovered in a Neolithic

gravesite alongside a trove of more rudimentarily shaped

counterparts, serves as a fascinating example of such

cross-cultural exchanges. Standing out in its refinement

and design, it is an apparent outsider among its peers.

Its presence here, in a setting dominated by more

crudely formed pieces, is intriguing and points to the

interaction and exchange between the Sahara's

hunter-gatherer societies and more agriculturally

advanced cultures.

This unique bead acts like a silent storyteller,

offering tantalizing clues about the interactions,

exchanges, and possibly, the barter practices between

distinct cultures and societies during the Neolithic

era. This bead is more than just an aesthetic piece; it

is a tangible trace of ancient cultural connections and

early commerce.

You can explore more about the remarkable journey and

origin of this bead by

following the link provided.

|

|

|

|

|

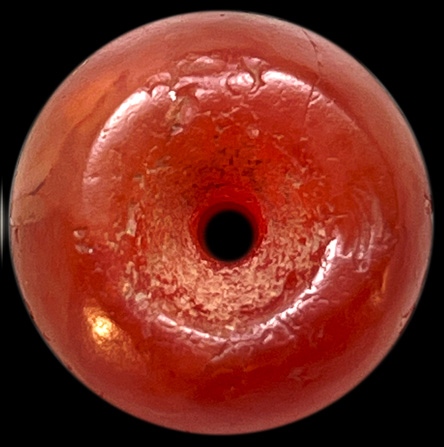

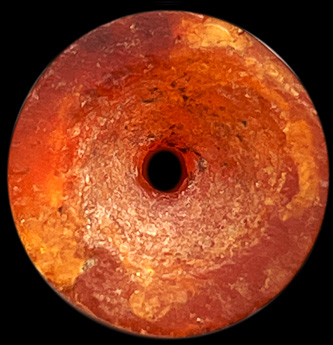

Early

Indus Valley tabular disk beads

Indus Valley is known for its remarkable

legacy of bead craftsmanship, and one of the most iconic styles from

this ancient civilization is the tabular disk bead. These early beads

are unique for their telltale marks of pecking, despite subsequent

polishing on a grinding stone - a feature common in beads from the

Neolithic period.

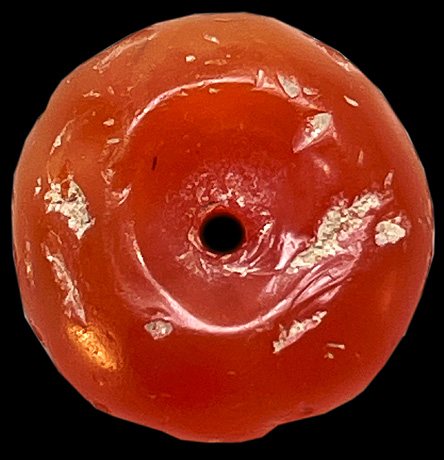

When you look at the beads presented below, one of the most striking

attributes you'll notice is the consistent, high-quality deep red

carnelian. These gemstones, notable for their lush, fiery hues, are a

testament to the exquisite taste and craftsmanship of the Indus Valley

civilization.

Carnelian, a semi-precious gemstone, was highly prized in the ancient

world for its captivating, radiant color. The choice of this material

not only reflects the technical mastery and aesthetic sensibility of

Indus Valley artisans but also gives us a glimpse into the cultural and

symbolic values of this early civilization.

Indeed, these early Indus Valley tabular disk beads, with their finely

honed shapes and distinctive coloration, bear the indelible mark of a

culture that truly understood and appreciated the art of bead making.

|

|

|

|

CARN

- OIV 3 -

Average size: 10 * 3 mm

Period:

Indus Valley Culture - Most probably the

Ravi Phase 3300-2800 BC

Origin: Harappa - Greater India (Now Pakistan)

The site

www.harappa.com, picture no.120

shows the same carnelian type of bead to the right.

Here is a photo from an excavation find from Bhirrana

where you can see the same disk beads.

(Archaeological Survey of India)

|

Below you can observe some of the more fine shaped beads in my Neolithic collection.

|

|

|

|

|

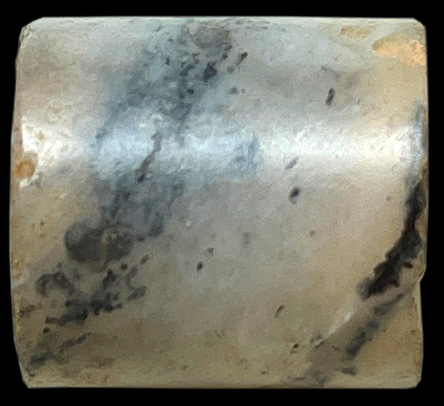

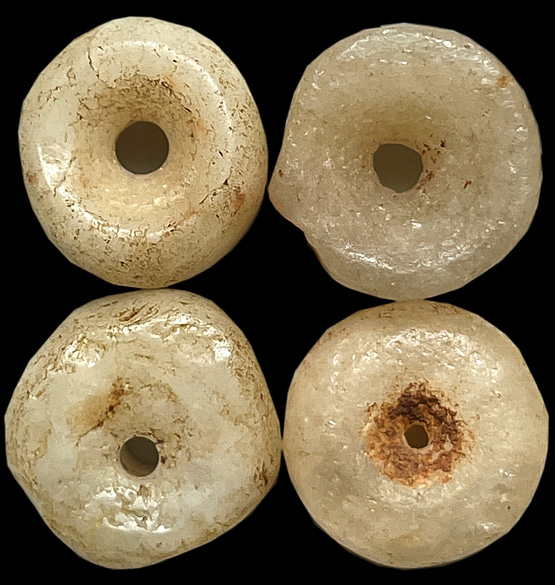

The drilling technique of Neolithic beads

The Neolithic beads were produced with the simplest tools! Here you can see the drills used for the pecking of the holes. The pecking was done from both sides of the bead.

|

|

|

|

|

Most beads from the Neolithic period are, as you can see on the picture below, not too long. They are

disk shaped.

|

|

|

|

|

|

The similarities between the beads discovered in

Neolithic graves in the Sahara and those originating

from the early Indus Valley are indeed remarkable. My

hypothesis is that these beads, often assumed to be the

creation of local Sahara cultures, may have been

produced by the more advanced Bronze Age civilizations

spanning from Persia to the Indus Valley.

These beads could have reached the Saharan region via

ancient trade routes, bringing with them the cultural

and artistic influences of their origins. They serve as

tangible pieces of evidence for early globalization,

revealing how objects of beauty and cultural

significance could cross vast geographical expanses,

even in ancient times.

A comparison of design elements, material choice, and

craftsmanship suggests a compelling connection between

these seemingly disparate regions. The refined shape,

skilled workmanship, and intricate detailing evident in

the Sahara beads echo the sophistication of beadwork

from the Indus Valley. Such intricate artistry was

characteristic of Bronze Age civilizations, underlining

the possibility of an intercultural exchange.

This theory could mean that a significant portion of the

beads found in Neolithic Saharan graves might not be

local artifacts but cultural imports from

technologically and artistically advanced civilizations

of that period. If this theory holds, it not only

reshapes our understanding of Neolithic Sahara but also

underscores the extensive reach of Bronze Age

civilizations like the Indus Valley.

However, further research, including metallurgical

analysis and isotopic studies, would be required to

confirm this hypothesis conclusively. These

investigative processes would help identify the material

origins of the beads, thereby validating or disproving

any links to external cultures.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Indus Valley Culture,

Ravi Phase 3300-2800 BC - 10 * 3 mm

|

When you look at the drills above it gives sense that the beads were mostly tabular. Drilling of long holes in long beads is very difficult and began with the Copper bronce age in West Asia and the Indus Valley. It became a goal in itself to make beads as

long and as slender as possible.

On the

Indus-sites we find a lot of broken beads that tells us that this kind of bead making was a difficult task to make elongated beads.

|

|

|

|

12 * 11 mm

|

In these more rare bi-conical carnelian beads, the pecking hole is uneven,

often taking shape like a hour glass as you can see below:

|

|

|

|

|

|

Here is a typical Neolithic hand grinding stone:

|

|

|

|

|

At that time all beads were hand grinded on these stones.

|

|

|

|

NEO 1 - 20,5 * 15 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 2 - 18,5 * 7,5 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 3 - 15,9 * 9,9 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 4 - 14,5 * 9,2 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 5 - 17 * 16 * 8 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 6 - 16,5 * 10 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 7 -

|

|

|

|

NEO 8 - 17 * 5 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 9 - 1,2 * 17,5 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 10 - 21 * 10,5 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 11 - 15 * 8 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 12 - 14 * 6 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 13 -

|

|

|

|

NEO 14 - 13,5 * 12 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 15 - 13,2 * 9 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 16 - 13,9 * 7,9 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 17 - 19 * 11,1 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 18 - 21 * 7,5 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 19 - 17 * 8,5 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 20 - 21 * 8,5 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 21 - 22,3 * 12,5 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 22 - 17,4 * 15 * 6,9 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 23 - 18,2 * 6,1 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 24 - 18,5 * 8,1 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 25 - 15 * 8 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 26 - 16,5 * 6,5 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 27 - 14,4/14 * 7,2 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 28 - 16,1 * 6,9 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 29 - 17,9 * 10,9 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 30 - 14,5 * 6,3 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 31 - 15 * 6,2 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 32 -

|

|

|

|

9 9

NEO 33 - 9,5 * 12 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 34 - 15 * 8,5 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 35 - 11,5 * 6,1 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 36 - 15 * 9 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 37 - 18,9 * 8,2 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 38 - 12,9 * 4,8 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 39 - 11,8 * 8,8 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 40 - 15 * 5 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 41 - 14,8 * 7 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 42 - 15 * 9,5 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 43 - 15,5 * 6,1 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 44 - 17 * 10 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 45 - 14,5 * 13 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 46 - 12,6 * 8 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 47 - 14,1 * 8,9 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 48 - 16 *8 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO -

|

|

|

|

NEO 49 - 14,3 * 13,3 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 50 - 15 * 11,5 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 51 - 10,2 * 8,2 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 52 - 13,5 * 9,8 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 53 - left: 11 * 8 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 54 - 14 * 10.5 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 55 - 12,2 * 6 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 56 - left: 12,8 * 6,5 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 57 - upper left: 15 * 5,5 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 58 - up: 12,2 * 6,1 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 59 - low left: 14 * 7,2 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 60 - low left: 11 * 5,6 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 61 - low left: 15,1 * 7 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 62 - 12;2 * 10 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO -

|

|

|

|

NEO -

|

|

|

|

NEO 63 - middle: 9,2 * 8,5 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 64 - left: 13 * 6 - right: 12 * 8,5 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 65 - 22 * 12 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 66 - 22 * 19 * 6 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 67 - 23,5 * 21 * 8 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 68 - 20 * 11,5 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 69 - 22,5 * 15 * 6 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 70 - 21 * 15 * 13 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 71 - 31 * 26,5 * 7 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 72 - 14 * 14 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 73 - 17 * 8,8 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 74 - 28 * 20 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 75 - 21 * 18,3 * 12,9 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 76 - 21 * 4 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 77 - 14 * 12 * 10 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 78 - 22,5 * 11,5 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 79 - 33 * 18,5 * 11,6 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 80 - 19,3 * 17 * 4,9 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 81 - 25,2 *19,2 * 7,9 mm - SOLD

|

|

|

|

NEO 82 - 31 * 20,9 * 9,5 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 83 - 18 * 5,9 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 84 - 23 * 15,9 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 85 - 26,1 * 18,9 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 86 - 25 * 9,9 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 87 - 17,1 * 5,3 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 88 - 21,5/21 * 6,3 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 89 - 19 * 11,9 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 90 - 14,5 * 13,2 * 9 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 91 - 13,9 * 8,5 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 92 - 20 * 9 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 93 - 13,5 * 13,2 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 94 - 12,8 * 11,4 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO -

|

|

|

|

NEO 95 - left low: 12,2 * 9,1 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 96 - left low: 14,6 * 8,2 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 97 - Low left: 15,5 * 10,1 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 98 - Low: 12 * 11,8 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 99 - Low left: 14,1 * 7,5 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 100 - low:14,1 * 10,5 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 101 - left: 11,8 * 7,3 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO 102 - 10,9 * 10,1 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO

103 -

13,9 * 8,9 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO

104 -

9 * 7,9 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO

105 -

8,4 * 8 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO

106 -

12,8 * 5,2 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO

107 -

Largest bead: 34 * 11 mm

|

|

|

|

NEO -

|

|

|

|

NEO -

|

|

|

|

|

|

|